An Open Letter to the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

“He drew a circle that shut me out- Heretic, rebel, a thing to flout. But love and I had the wit to win: We drew a circle and took him in!” Edwin Markham, from “Outwitted”

Introduction

In your piece, “Examining the House Agriculture Committee’s Reconciliation Bill,” (June 4, 2025, https://sustainableagriculture.net/blog/examining-the-house-agriculture-committees-reconciliation-bill/,) you write that the House Agriculture Committee’s Reconciliation Bill” “boasts an immediate increase to reference prices for each covered commodity under the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program by 10 to 20%, in addition to an annual 0.5% adjustment beginning in 2031, up to 115% of the statutory reference price.” And you are boasting this too, but as a bad thing. And you’re relying on FarmDoc Daily in your analysis.

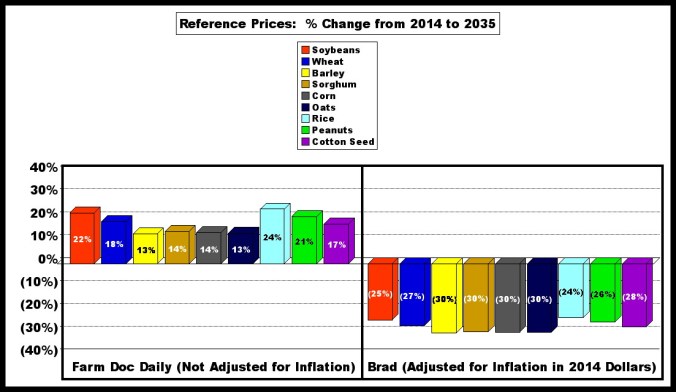

Doing the Math Correctly: Adjusting for Inflation

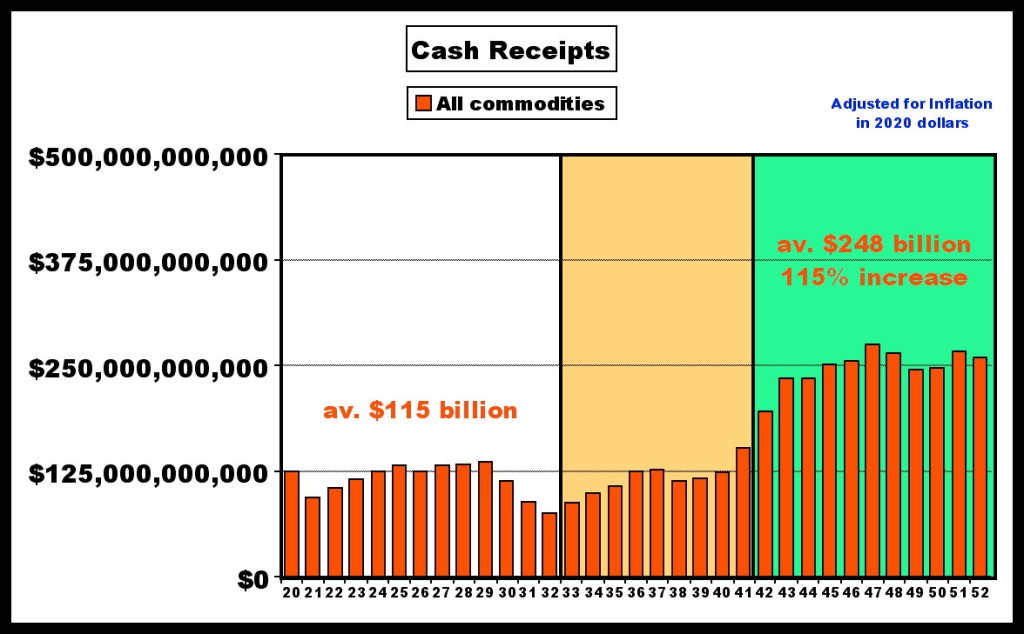

But there’s a problem here. None of you did the math correctly. None of you adjusted for inflation. When you do that with regard to the PLC program, then the benefits have gone down every year, and they will continue to go down in the Republican bill. So yes, there’s an increase in Reference Prices from 2024 to 2025, for example, but prior to that the 2014 statutory Reference Prices, (continued in 2018,) have fallen considerably, to just 77% of the 2014 level. Adjusted for inflation in 2014 dollars. So the new 2025 levels are actually significantly lower than 2014, with corn, for example, at only 83% of 2018. And this reduced level then goes down every year, 2026-2030 for the same reason. You point to the “annual 0.5% adjustment beginning in 2031,” and call it “115% of the statutory reference price.” But CBO projects a 2% rate of inflation for those years, so the 0.5% increase is actually a 1.5% decrease. In calling it a 115% increase, (113.5% for corn,) you’re comparing the new nominal 2035 Reference Price with the old nominal 2014 Reference Price. But if you adjust for inflation, (i.e. in 2014 dollars,), corn is only 70% of the 2014 level, as is oats, barley and grain sorghum. Most others are not far behind.

The Larger Contexts of Market Management Policy Reductions, the Full Costs of Production, the Farm Economy, Agribusiness, and the Republican Party

What makes you think that Republicans would ever do anything significant to help farmers? Republicans have a long history of making things worse, including for corn, wheat, cotton rice and soybeans. With that in mind, there are other problems here as well, such as the lack of an adequate context for the changes and impacts. In creating and supporting the PLC program, (2014 & 2018 farm bills,) Congress set reference prices well below the full costs of production in most cases, (i.e. excepting rice and peanuts). That’s where the downward trend lines start, at the low 2014 levels. I computed this for the initial standards 10 years ago, (2014, 2015,) and I’ve now computed it for the earlier phase, through 2025. I’ve also taken 2025 full cost figures and projected them ahead using CBO’s projected rates of inflation. Again all crops except peanuts and rice are consistently below full costs, (and peanuts and rice fall below full costs at times, as their Reference prices fall year after year).

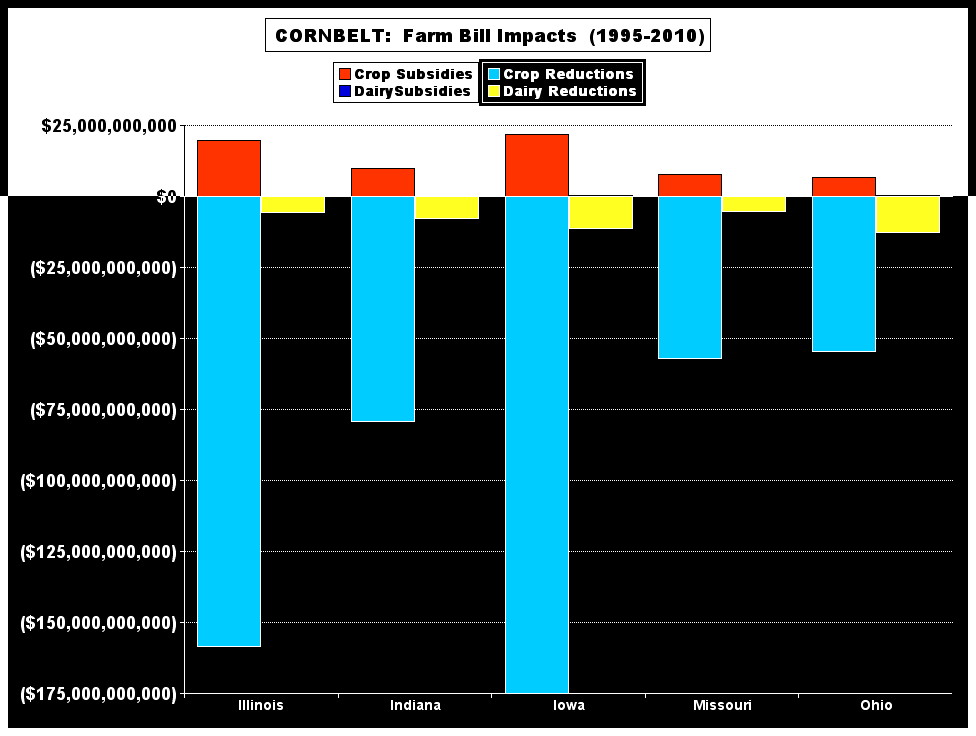

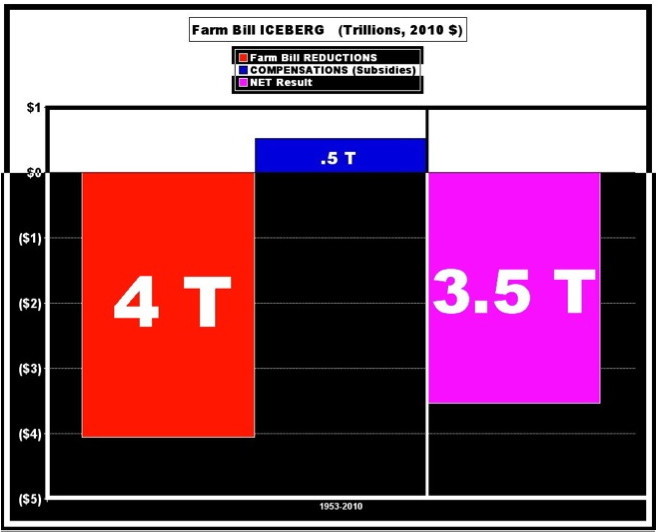

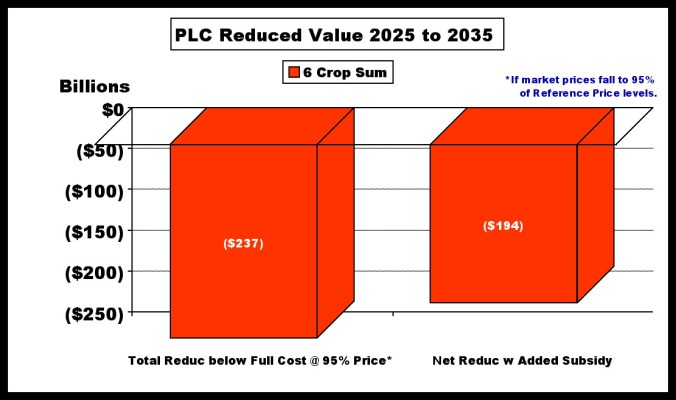

Here I note that you translate the Republican farmer benefits from things like Reference Prices, (i.e. in dollars per bushel,) into billions of dollars. You refer to an increase of “roughly $52 billion over 10 years.” My calculations are based upon CBO projections of PLC participation rates, PLC historic or “payment yields,” and market prices, as well as projected full cost figures. I look at just 6 crops, corn, soybeans, wheat, barley, oats and grain sorghum, because those are the only crops for which CBO has provided projections of participation rates. I used an example where market prices fell to 5% below reference prices, where the PLC subsidies clearly kick in. Figures are adjusted for inflation in 2025 dollars. What I find at those price levels is a reduction of $237 billion below full cost estimates for the 6 crops, for 2025-2035. (Of course there were billions in reductions during the earlier phases as well.). Then, when PLC subsidies are calculated, the reductions are reduced to just $164 billion below zero.

So the subsidies figure to be $43 billion in the example. Of course, this would all be bigger if I had comparable projections for the additional crops.

Ok, so net benefits at $164 billion below zero. Here again, the money, (in this case the big billions,) looks very different when you adjust for inflation, and place the figures in the larger context of economic realities.

You further argue that “very few farms will benefit from the bill’s most expensive agriculture provisions,” including, for example, “Farmers growing fruits and vegetables – among them, many small and direct-market farms.” And, you add the specific context, of how “78 percent of counties stand to see a net reduction in federal nutrition benefits” from the farm bill changes. But what my math has shown, is that the Republican programs massively reduce benefits for the farmers using the PLC program.

Us Against Them

Strategically and politically, in making these arguments, you’re emphasizing a division between the many farmers in programs like PLC, (falsely said to have increased Republican support,) and sustainable, local farmers, fruit and vegetable farmers, and poor people. It’s them against the PLC farmers. What I’ve shown, however, is that you’re blaming farmer victims, and that you are therefore pitting victim against victim. It’s an “us against them” mentality. In this you lump farmers and Republicans together, as if they’re close allies. By your criteria, most farmers in many midwestern states should vote Republican. So I guess you’re saying that, with regard to economic interests, Republicans should win the rural vote. It’s a recipe for over all farm interests, (in sustainability AND justice,) to be divided and conquered. It’s a major part of how those advocating on farm issues have become siloed, doing their own thing separately. That’s according to your math, and that of sources like FarmDoc Daily. That’s according to not adjusting for inflation, and not considering the larger economic, strategic and political context.

The Historical Context Behind the NSAC’s False Paradigm: What the Evidence Shows

There is, however, an additional and much larger economic, strategic and political context left out of your analysis. This is that you don’t account for how agribusiness will benefit from the bill. This is an issue that reaches back to the origins of major campaigning by the Sustainable Agriculture Movement during the 1990s, following decades of activism on the issues of economic distributive farm justice by the Family Farm (Farm Justice) Movement. With help from large funding sources, sustainability rose up and justice sank down, (with help from Republicans ending market management farm programs in the 1996 farm bill, ‘free’ trade agreements that assaulted farm justice globally, the rural populist Democrats switching sides to join Republicans in “greened up versions” of the 1996 bill, and a major reduction in the funding of farm justice organizations.

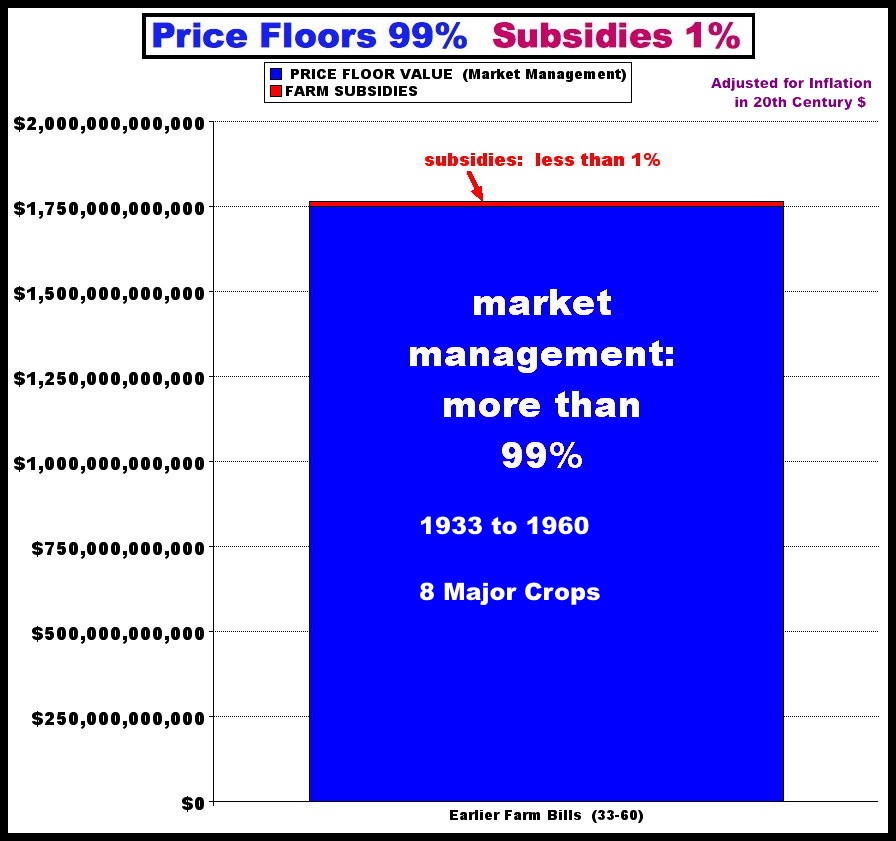

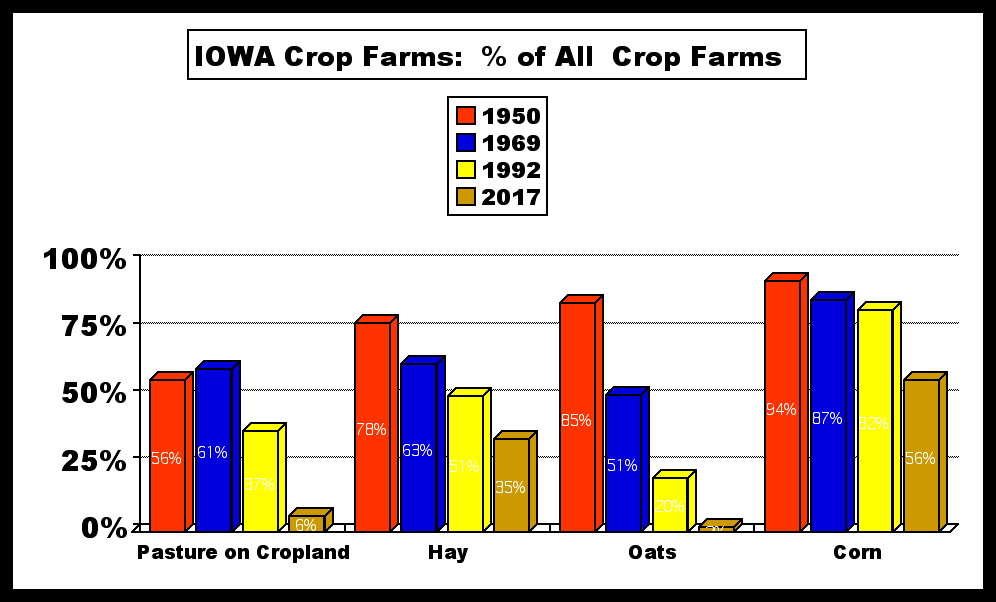

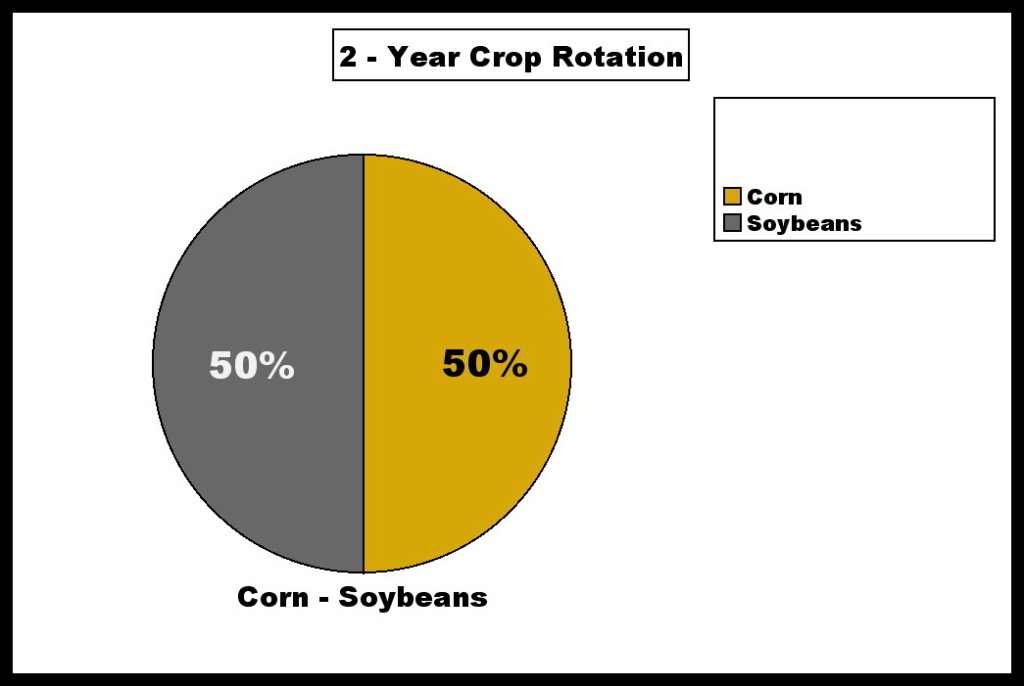

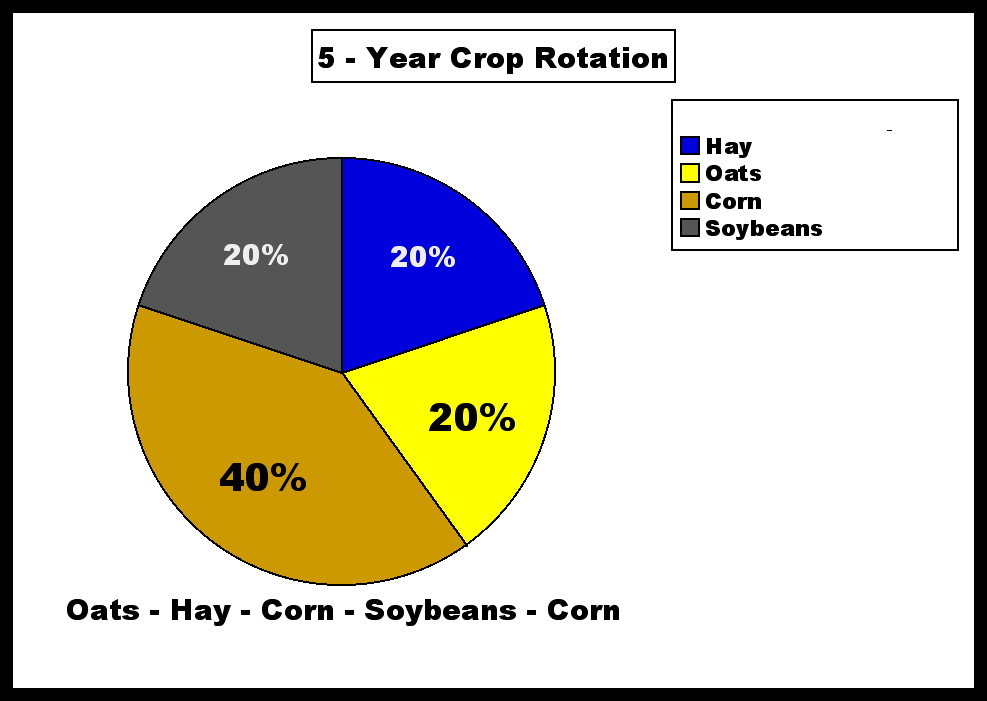

I was there, with others, in 1995 when NSAC’s predecessor, the National Campaign for Sustainable Agriculture (NCSA) was being formed, (participating on committees of the Midwest Sustainable Agriculture Working Group and the new national umbrella group). I spoke out in favor of the policies of economic justice, which were being neglected by the top leaders of the movement. Specifically, I called for the groups to take a united stand for adequate levels of the Price Floor/Supply Management programs, (no subsidies needed). These changes would have ended the massive agribusiness/CAFO subsidies, reduce acreages of corn and soybeans, and support crops like oats and barley, (which in turn support the use of pasture and hay, grass, alfalfa and clover, in resource conserving crop rotations).

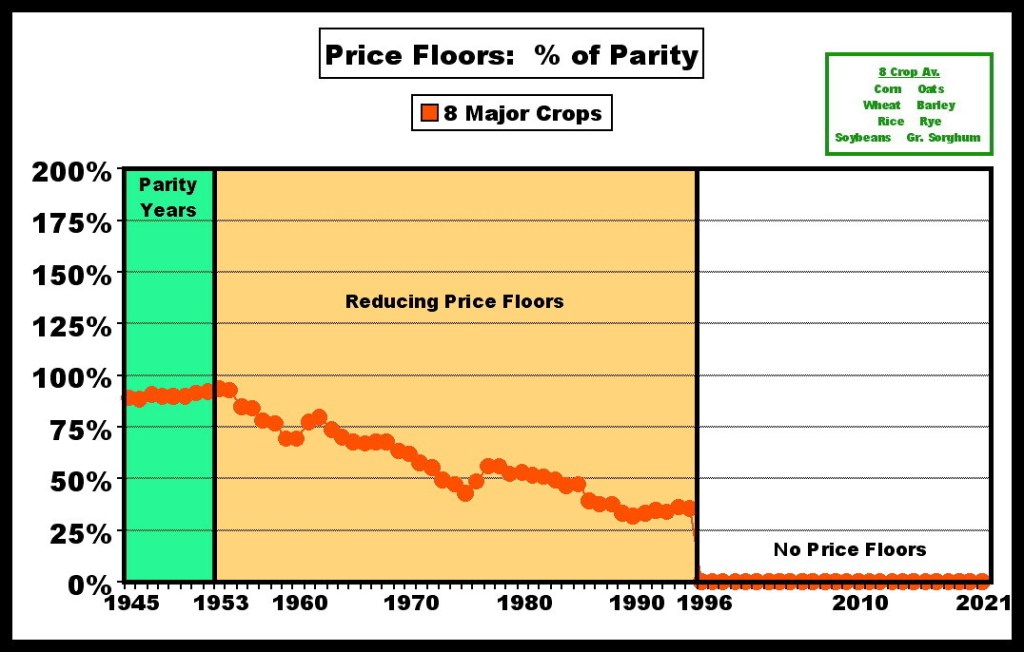

NCSA rejected these changes. Later, however, mainline churches convened a meeting to take a second look at these issues, however, and the proposals to end agribusiness/CAFO subsidies were supported. Shortly afterwards, however, key leaders back home blackballed this agreement, and that has been NSAC’s position up to today. Meanwhile, Republicans in Congress ended the Price Floor programs, (signed by President Clinton,) leading to 8 of the 9 lowest corn and soybean prices in history, 1997-2005. Additionally, as billions of additional dollars were transferred from feed grain and soybean farms to CAFOs, damage to sustainable crop rotations has continued, with farms such as here in Iowa losing more livestock diversity, to then lose more of the diversity of sustainable livestock crops, pasture hay and oats.

These cheap conventional prices also lowered the standards undergirding organic premiums, and the competition in stores against those sales. This occurred for dairy as well, as those low price floors were ended. Local sales of meat and dairy here in my town, (after investing in infrastructure for processing and marketing,) didn’t last very long under those conditions. The massive loss of livestock and “livestock crop” diversity since 1950 has also led to a massive loss of the infrastructure for diversity, on farms, in rural communities, and across rural regions. (Loss of fences and livestock facilities, loss of support services and equipment including large animal vets. My elevator quit grinding feed and quit buying oats.) That too hurts organic farmers. At the same time, surviving farmers continued increasing the number of days they worked off the farm and the amount of non-farm money they made, increasing the availability of off-farm capital, and decreasing the availability of the labor needed for diversity. This all contributed to the failed system we have today, and to the tremendous problems of agriculture, including the environmental and health problems.

Your Paradigm is Too Small

The issues here are clearly systemic. They’re based upon an inadequate paradigm, a false dominant narrative, (actually interrelated false conservative and progressive narratives that have deep roots in the farm subsidy question). The view of the Sustainable Agriculture Movement during the 1990s, (like the one you’ve put forth here,) was based upon a belief that the trend away from sustainability was caused by greatly rewarding crops like corn and soybeans with “commodity subsidies.” The logic behind this claim is that you only need to look at subsidies and spending to know what caused the problems. From that perspective you then conclude that corn and soybean farms have been greatly rewarded, leading to all of the problems.

By that same logic you only need to look at spending on SNAP subsidies to know that SNAP recipients are the biggest winners of the farm bills. Additional aspects of the logic of this false paradigm would then lead to conclusions such as: SNAP recipients and Big Food are on the same side, and SNAP recipients are likely among the biggest lobbyists funding Congress. (These absurdly false claims are directly equivalent to those made about “industrial farmers,” such as those growing corn and soybeans.)

In both cases, the paradigm is far too small. You need to look at the larger economic and policy context to understand what farm and food subsidies accomplish. As it turns out, SNAP recipients are poor, and SNAP has been inadequate, in that context, to prevent many children and adults from going hungry. The missing policy context is that of market management. For SNAP recipients, that includes low minimum wage floors, (projected to fall into the $4 range in 2026, adjusted for inflation in the original 2009 dollars). Other factors include weak labor laws, lack of full employment policies and programs, lack of fair trade agreements, and lack of adequate anti-trust policies and enforcement.

The same holds for the logic of NCSA’s and NSAC’s interpretations of farm subsidies. The main specific market management policies and programs, Price Floors and Acreage Reductions, were reduced, more and more, 1953-1995, then ended. Along the way, market prices dropped more and more, net farm income went low and stayed low, and similar results are found from a list of major economic indicators. Meanwhile, subsidies didn’t start for corn until 1961, after prices had already dropped a lot. Soybean commodity subsidies didn’t start until 1998, (i.e. no Deficiency Payments). So there were had been no subsidy compensations for soybeans as of the 1990s when NSAC leaders blamed subsidies for over-rewarding soybeans.

I examined corn and soybean prices and subsidies for 1980-2005 using percent of parity. This enabled me to directly compare what happened to them with what happened to other enterprises that are important to resource conserving crop rotations. As it turns out, by this standard, corn and soybeans made less, (prices plus subsidies,) than cattle, dairy, hay and oats, (adding in subsidies only for corn, soybeans and oats). All of these crop and livestock prices went downward during the period, however, (and from 1953 to today). So in fact, sustainable crop rotation enterprises were more rewarded, (less reduced,) than corn and soybeans during this period that played such a major role in affecting farming systems. The finding here is that the claim that corn and soybeans more incentivized than sustainable enterprises is false. The increase in corn and soybean acreages actually resulted from the increased penalization of corn and soybeans over the decades and the greater penalization in comparison to the penalization of other farming enterprises.

The same holds for fruits and vegetables. Market prices for 45 fruits and vegetables, (counting no subsidies,) were consistently lower than market prices for corn, soybeans, wheat, rice and cotton, (adding in subsidies for these 5 crops,) measured as percent of parity, (1953-2014 or 2015). (Here again, all crop prices fell, more and more over the time period.) So fruits and vegetables, (not corn and soybeans,) were more incentivized, (less reduced). Here again, farmers raising the five subsidized crops got less and less, even with the added subsidies.

Further Implications

In pitting farmers against SNAP recipients there are other factors to be considered. It’s not fair that farmers should be singled out to be penalized with reduced subsidies in order to subsidize the hungry. Instead, they should receive living wages and other market management benefits, (including healthcare benefits,) which would significantly reduce the need for SNAP spending. Likewise, it’s not fair that farmers raising food products should be signaled out to be paid less, (including fruit and vegetable farmers,) in order to subsidize SNAP recipients through the marketplace. Living wages, for example, need to be high enough to compensate for fair farm prices, and minimum farm price floors should be high enough to compensate for workers, (producing inputs and items needed for farming and living,) being paid living wages.

There is also another factor which seems to be known only by the Family Farm (Farm Justice) Movement. I refer here to the top side of market management farm programs, maximum Price Ceilings to trigger the release of stored Reserve Supplies, as needed to prevent price spikes which raise the cost of food and other items. This protects the hungry poor, as well as livestock and poultry farmers using grain, and also related industries. This is especially important in this time of climate volatility. NSAC should support these programs.

Finally, with adequate Price Floors and Supply Reductions, no subsidies are needed, so these farm justice programs free up lots of money for SNAP and programs for conservation, local food, etc.

Conclusion

From within this larger, more evidence based, logical and adequate paradigm, it turns out that we’re really all united, local, organic, and conventional farmers, and environmental, hunger, anti-CAFO, and public health interests. We’re united, not divided, in the larger farm justice paradigm which holds agribusiness accountable, and which ends the harmful CAFO subsidies that corn, soybean and oather farmers have been forced to pay.

For Further Reading

Brad Wilson, “Republicans Reduce Farm Program Benefits, Again,” Family Farm Justice: 6/28/25,https://familyfarmjustice.me/2025/06/28/republicans-reduce-farm-program-benefits-again/. Includes a reference list to additional sources.

Brad Wilson, “Subsidized Crops vs Vegetables,” SlideShare: Brad Wilson, 11/14/20,https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/subsidized-crops-vs-vegetables-pt-i/239258118.

Brad Wilson, “Subsidized Crops vs Fruits,” SlideShare: Brad wilson, 11/14/20,https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/subsidized-crops-vs-fruits-pt-2/239258054.

Brad Wilson, “How CAFOs are Subsidized,” YouTube: Fireweed Farm, 4/30/25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7IaANx08G8&list=PLA1E706EFA90D1767&index=4.

Slide shows on the dozens of farm subsidy myths. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ZIOiwv1Nr6jn9SsnE62z1P_hitZKTBaD

Brad Wilson, “Cap Farm Subsidies at $250,000, or $25,000, or $0?”, 7/18/15, https://znetwork.org/zblogs/cap-farm-subsidies-at-250000-or-25000-or-0/.

Brad Wilson, “Don’t Grow Clover, Hay, Oats, (Corn)? De-Bunking a Farmer Bashing Myth,” ZSpace: Brad Wilson, 3/12/13, https://znetwork.org/zblogs/don-t-grow-clover-hay-oats-corn-de-bunking-a-farmer-bashing-myth-by-brad-wilson/.