House Republicans have proposed to reduce farm program benefits in the farm bill section of their big brutal budget reconciliation bill. Democrats should raise up this issue politically, in order to take back the rural vote, where so many states have become more Republican in recent years.

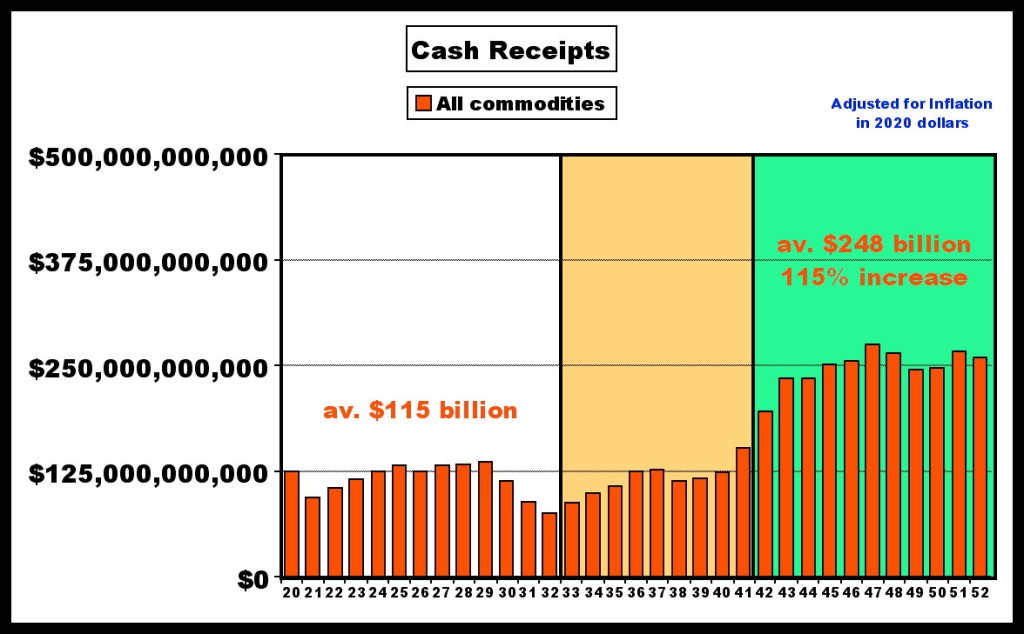

The Failed Farm Policies of the Anti-Farmer Republicans

(To see what the House Republican Reconciliation Bill did, skip ahead to the heading “Proposed Republican Reductions for the Price Loss Coverage Program.”)

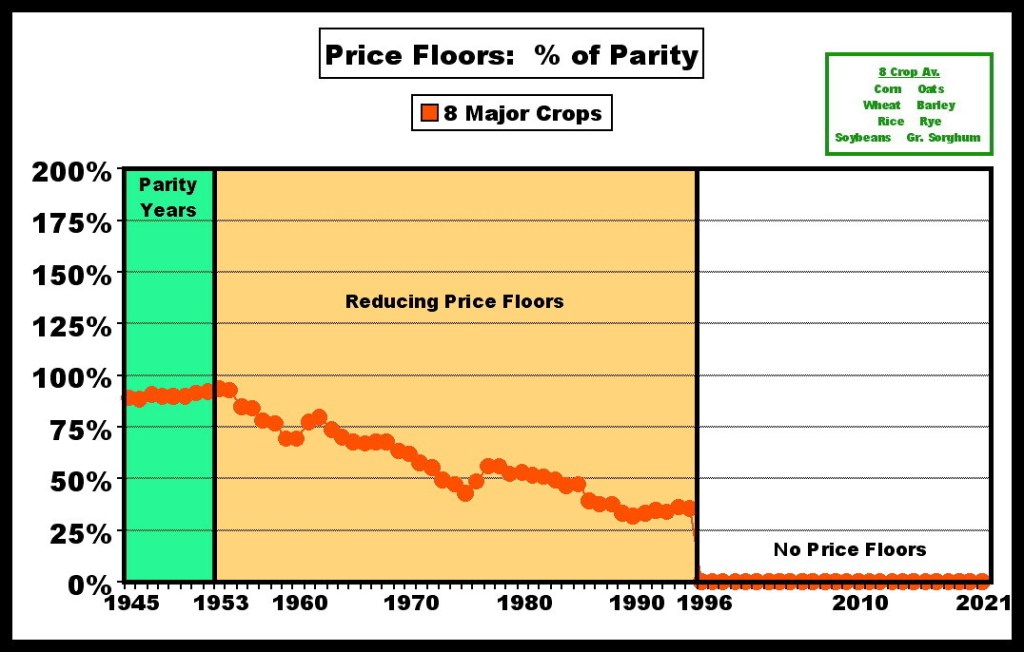

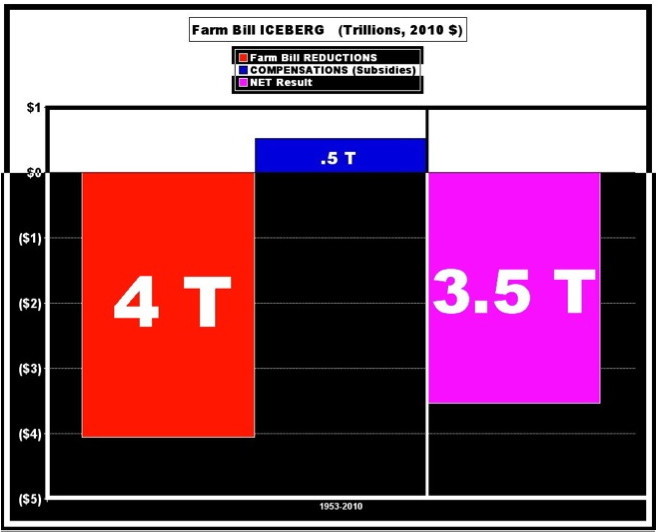

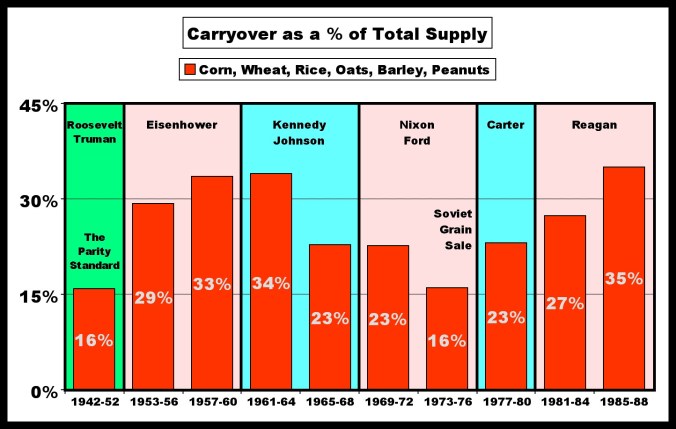

Over the long haul, as farm program benefits have been reduced more and more and more, Republicans have been the top leaders favoring the reductions. Republican farm bill actions have clearly been increasingly anti-farmer for seven decades, as they’ve reduced and ended the parity farm programs of the Democratic Party New Deal.

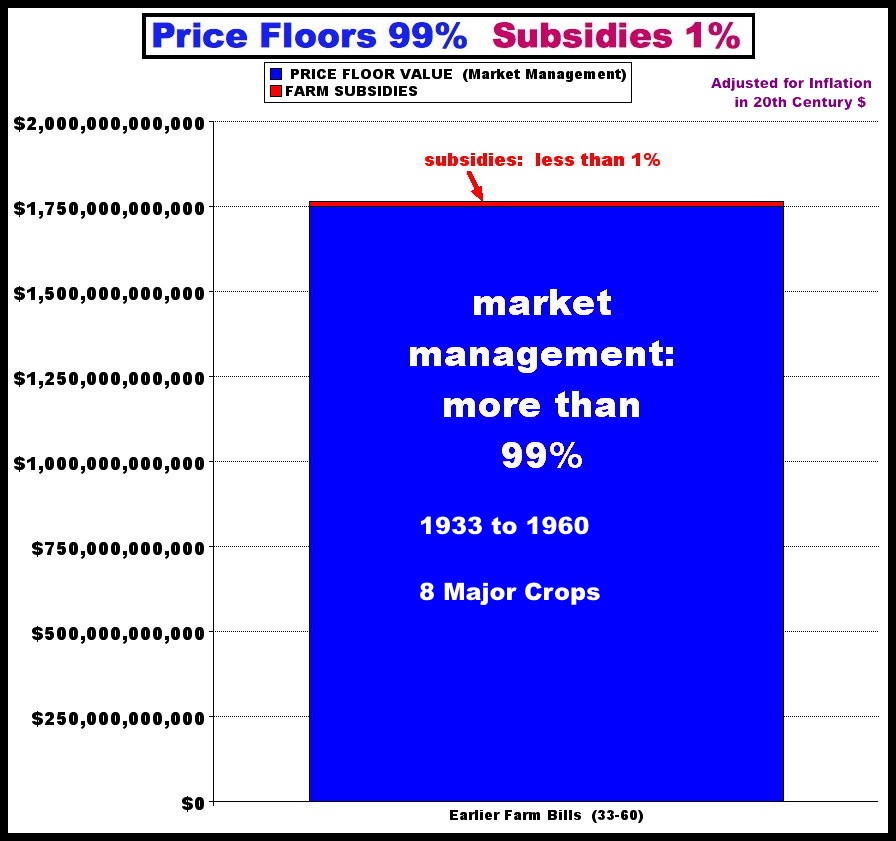

By the 1980s it was clear what the differences were between Republicans and Democrats on the farm bill. Republicans called for reducing minimum farm Price Floor levels, (similar in principle to minimum wage floors,) and starting in the 1950s, they consistently mismanaged supply management programs, especially supply reduction programs, causing increased oversupply and cheaper prices. Democrats managed the programs more effectively, consistently reducing oversupply.

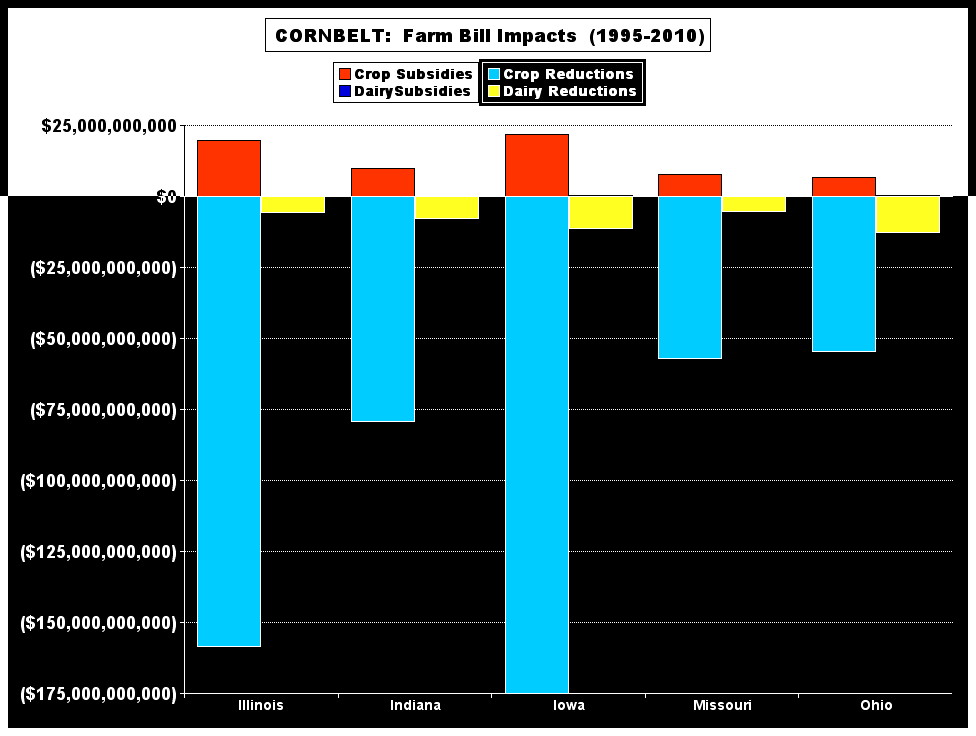

Especially during the 1980s phase of this chronic farm crisis we saw how the Republicans favored farm subsidies, which were not needed under the New Deal programs, which featured higher minimum farm price floor levels. So Republicans became the “big spenders.” During this phase, the chronic farm crisis had snowballed, leading to so many farm foreclosures that collateral values crashed by 45%. Returns on equity for the corn belt fell to double digits below zero for six years in a row. In response, in the 1985 Farm Bill, Republicans further lowered price floor levels by large amounts. They also greatly increased subsidies, but by a lesser amount than the price floor reductions, resulting in lower farm income.

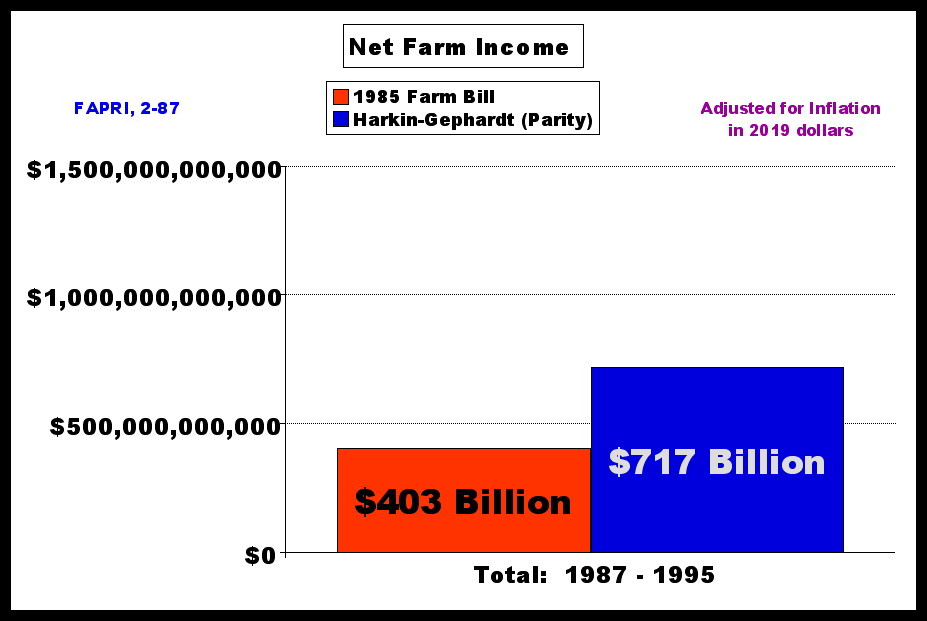

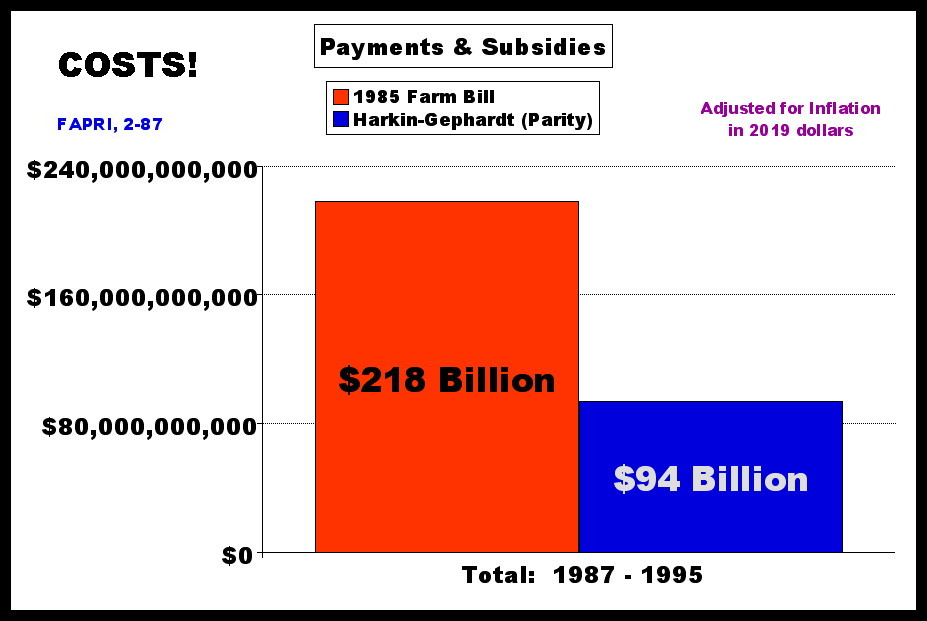

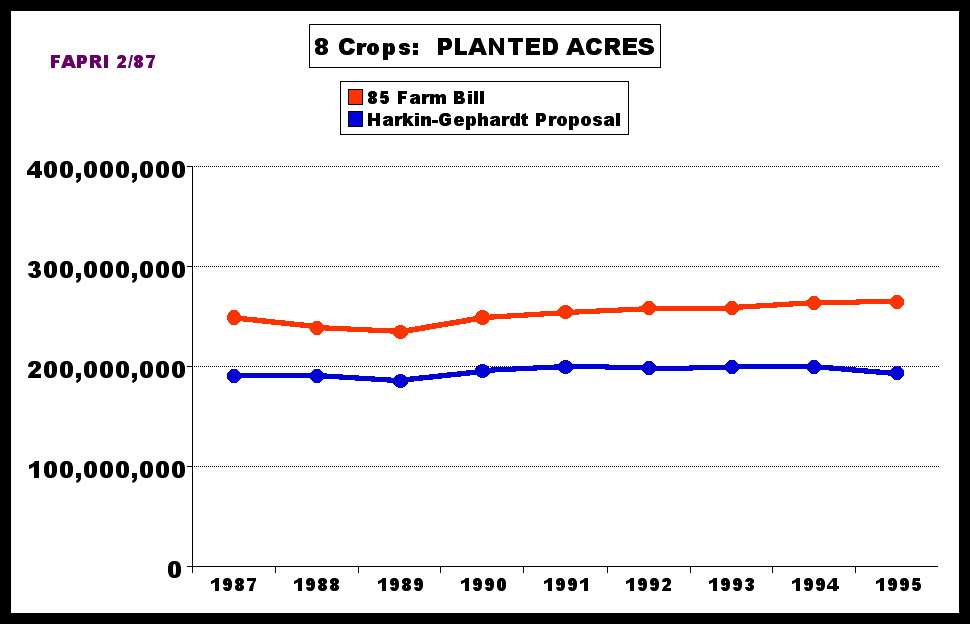

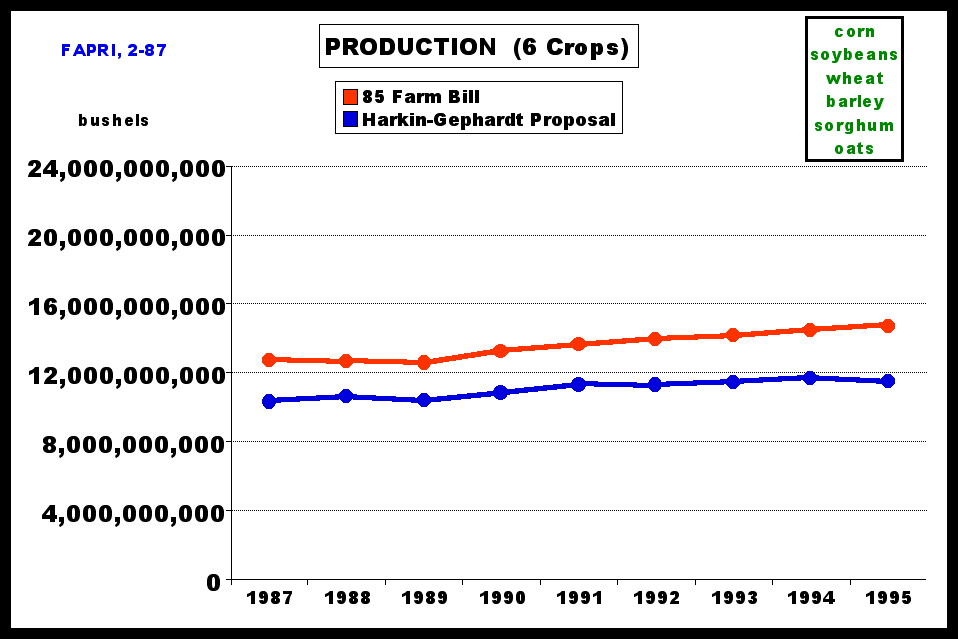

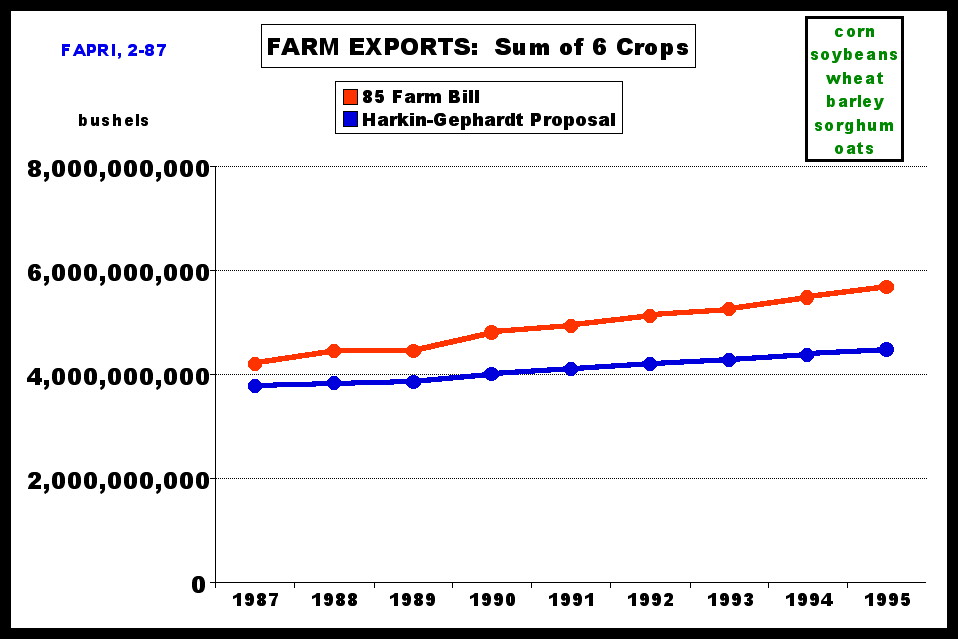

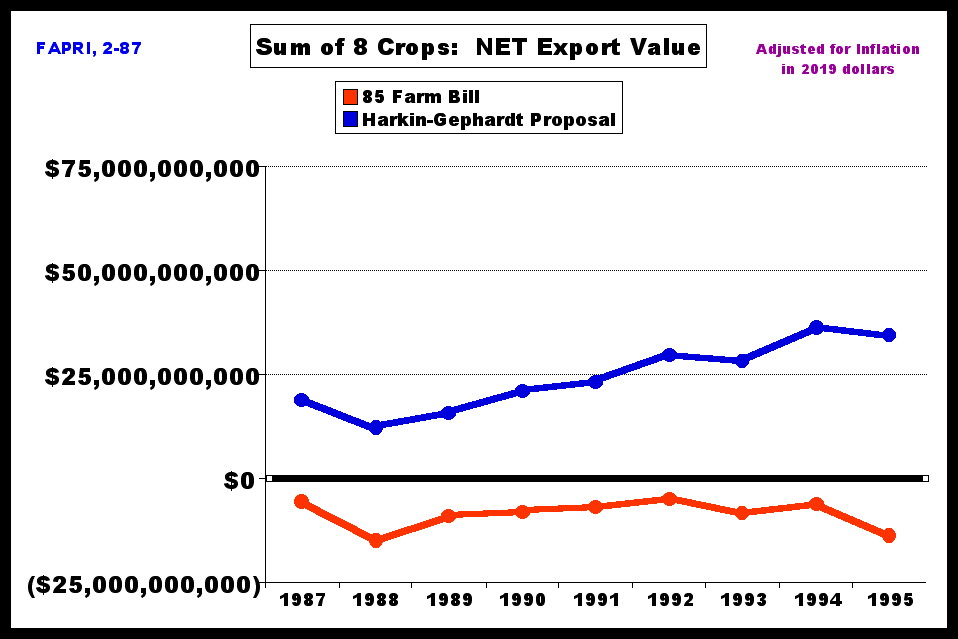

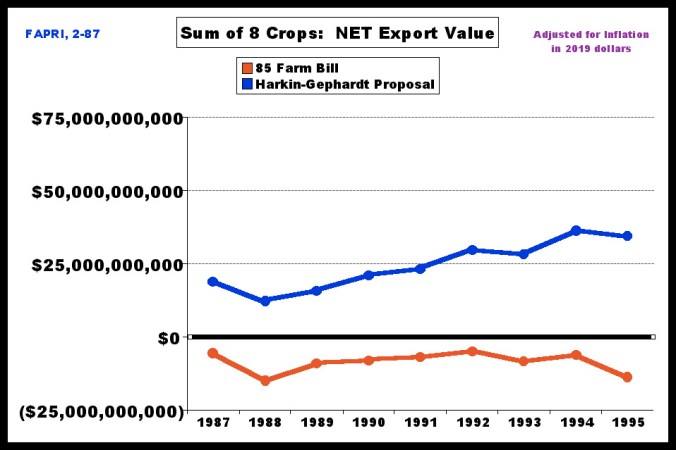

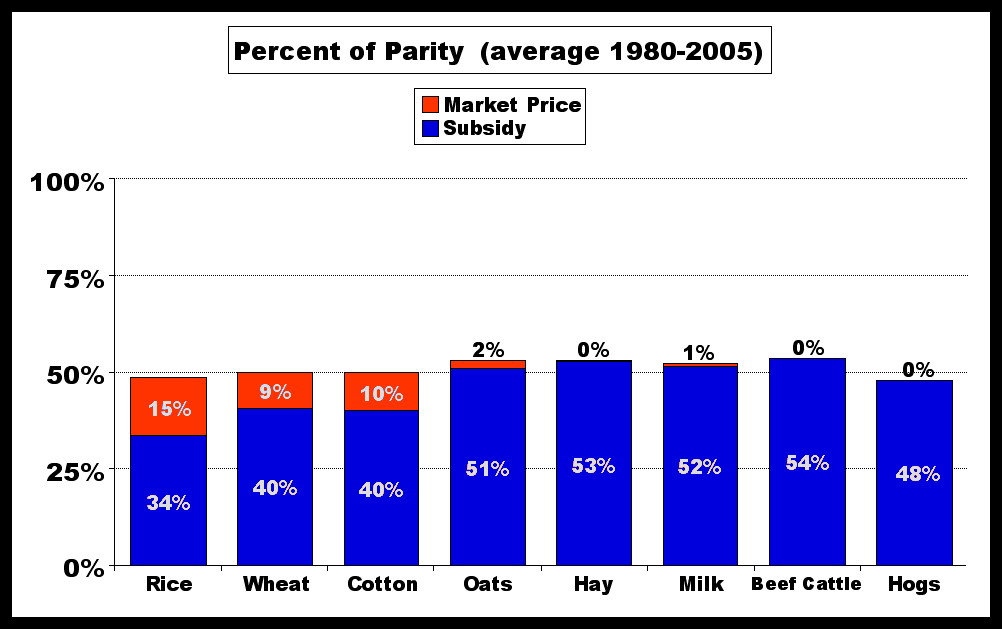

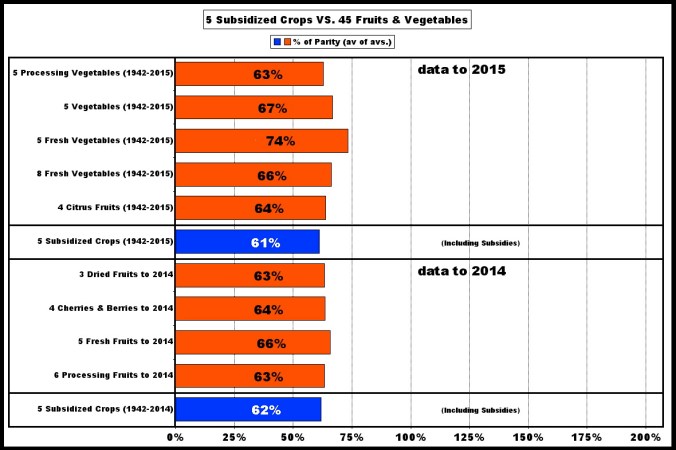

In contrast, during the 1980s and 1990s, rural populist Democrats proposed to restore New Deal Programs, reducing oversupply, raising price floor levels and with no farm subsidies needed. Examples of this include the Harkin-Alexander Bill of 1985 and the Harkin-Gephardt Bill of 1987. Econometric studies of these proposals, in comparison to the 1981 and 1985 farm bills found them to be much cheaper and much better for struggling farmers, with much greater income on farm subsidies. The Democratic proposal would have raised farm prices above full costs, and the U.S. would have stopped losing money on major farm exports, (with the losses falling on farmers, not the giant agribusiness middlemen). These efforts proved to be helpful to the Democratic Party across the major crop farming states.

The Democratic Farm Bills of the 1980s failed to pass in Congress, v, and major farm prices were below full costs every year, 1981-2006, except for 1996.

Then, in 1996, Republicans ended market management programs, (vetoed, then signed by Democratic President Clinton), while offering “transitional subsidies” for 1996 through 2001. These additional reductions almost immediately and massively failed, as farm prices fell to record low levels, year after year. For example, farmers saw 8 of the 9 lowest corn and soybean prices in history between 1997 and 2005, and other major crop prices were very similar. This created a huge crisis for the Republican Party. Instead of restoring market management programs, however, they poured in a lot more subsidy money, in 4 emergency farm bills, in 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001. These extra subsidies were then included in the 2002 Farm Bill. They were then reduced in the 2008 Farm Bill, and even more in the 2014 and then 2018 Farm Bills.

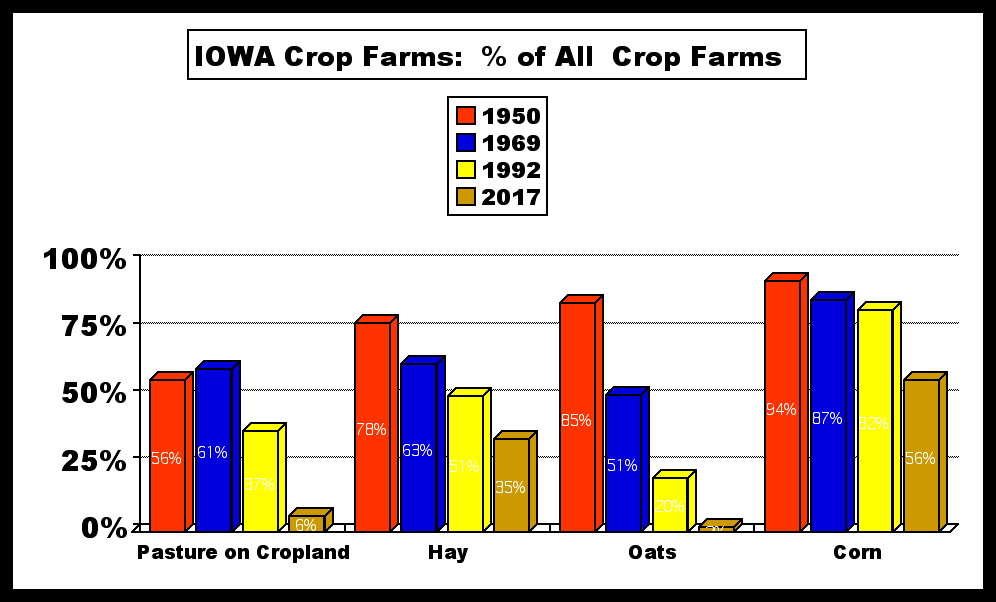

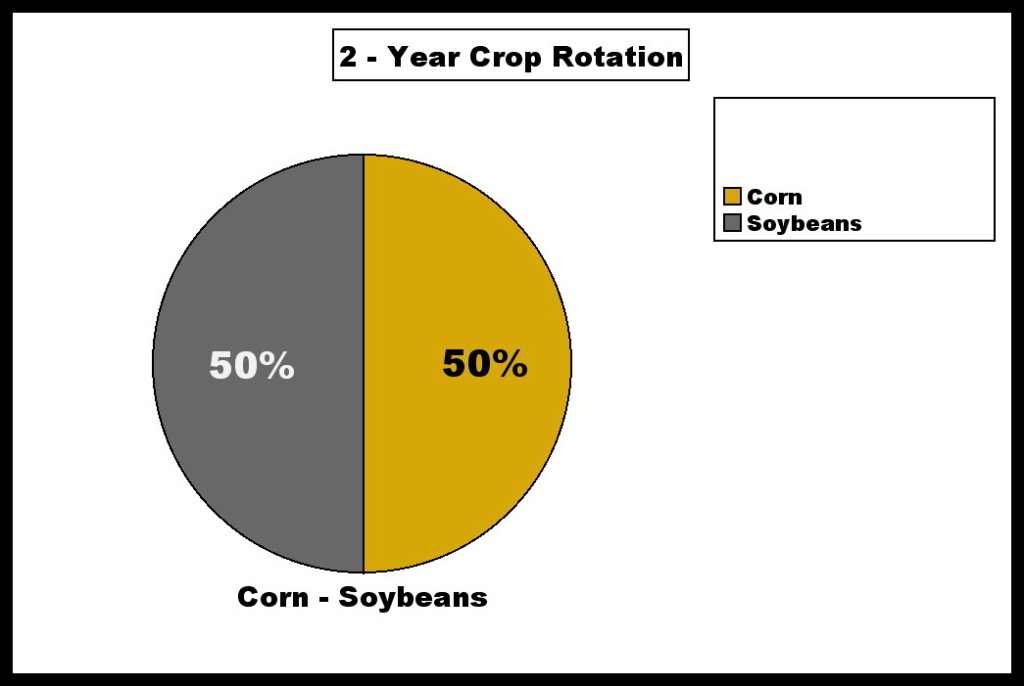

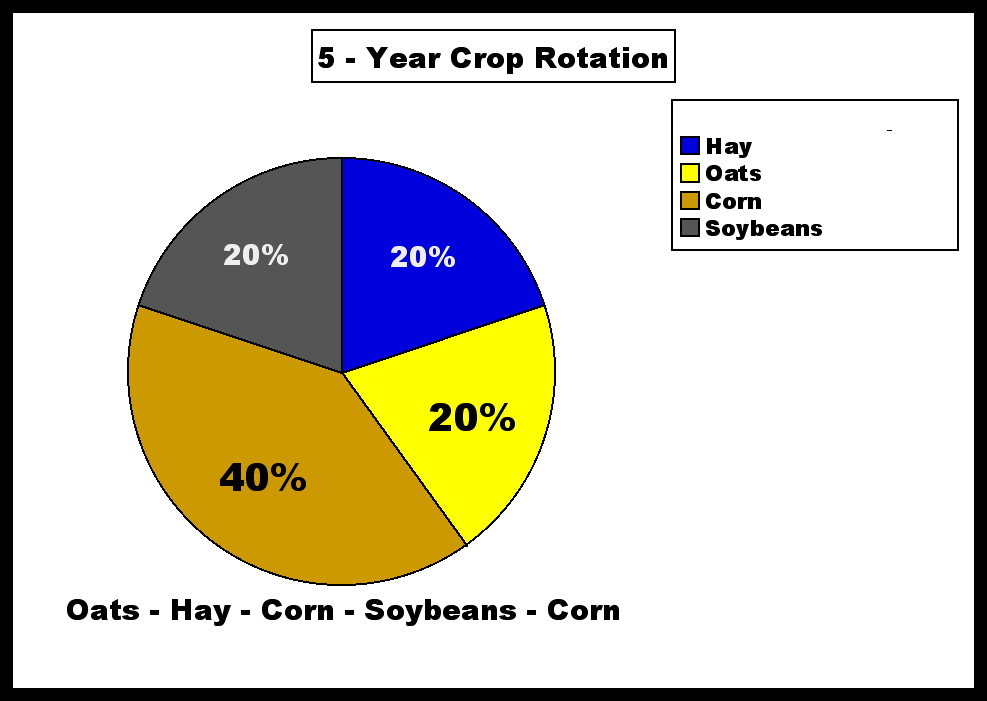

Meanwhile, in 2001, Iowa Senator Tom Harkin became Senate Agriculture Chair, and Harkin then led the populist rural Democrats in switching sides, and supporting a slightly greened up version of the 1996 Republican Bill. (I call this “The Harkin Compromise,” and see the reference below.) This “bi-partisan” (Republican) approach then became normalized, and farmers then had virtually no one in Congress to support them on these, the biggest farm policy issues. What Congress did was all for cheap farm prices the giant agribusiness/CAFO buyers, U.S. and foreign. Additionally, in multiple ways, it supported the giant agribusiness input sellers, as supply reduction programs were ended, and most farmers lost all value added livestock, to then lose all of the sustainable livestock crops, grass pastures and alfalfa and clover hay, plus the nurse crops for these, like oats and barley. The results have been devastating for the environment.

Harkin surely believed that switching sides was the right thing to do for the Democratic Party, as he was being criticized for proposing his version of the New Deal farm programs. (Republicans believe that free markets work for agriculture, and that’s the justification for the program reductions. That belief is untrue, however, and especially for agriculture, which “lacks price responsiveness” “on both the supply and the demand side for aggregate agriculture.”) We can see now, however, that since Democrats have stopped supporting fair prices for farmers, they have gone down a lot with regard to winning the rural vote. For example, Iowa has lost all of its Democratic members of Congress.

The Price Loss Coverage Program

Among the farm bill provisions in the House Budget Reconciliation Bill are cuts to the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) farm subsidy program, which is what I’m examining here. PLC is a “countercyclical” farm subsidy program, meaning that it’s the least irrational of these programs. This means that farmers get more subsidies when the need is greater, and less when the need is smaller. The program features subsidy triggers, dollar amounts per bushel, pound or hundredweight, below which a subsidy is given. The subsidy trigger levels are a called Reference Prices.

Here’s an example of how it works, which was given to me by Iowa Republican Senator Charles Grassley a few years ago at a town hall meeting. The PLC subsidy trigger for corn was set at $3.70. If the market price of corn fell to $3.32, then farmers who signed up for this program would get a subsidy. Grassley claimed that they would get the difference, 38¢ per bushel, but that is false. The formula for subsidies includes a 15% reduction, or 85% of the 38¢, (32¢,) and this is then multiplied by a farmers historic yield, (called the PLC Payment Yield). This is based on yields farmers got in the past, which are much lower than current yields. So the per bushel subsidy for the 38¢ reduction below the standard would be 22¢ per bushel. That is then multiplied by base acres, which are generally similar to actual acres of the crop.

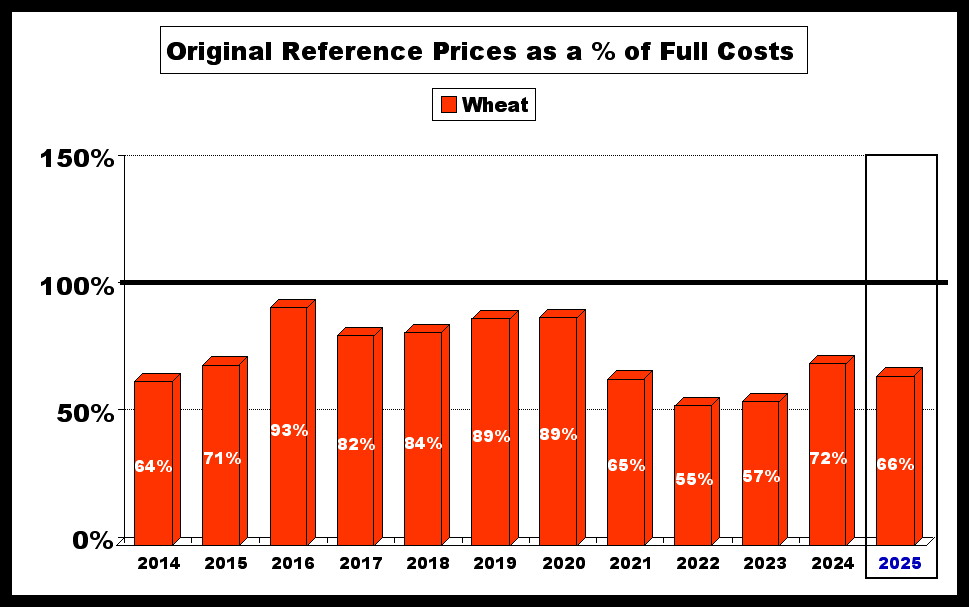

Reference Price standards were set in 2014, with no adjustments for inflation, so the same dollar amounts were used every year, 2014 through 2024. Of course, not being adjusted for inflation, the value of the standards fell lower every year.

Additionally, these subsidy trigger standards were set well below the full costs of production for corn, soybeans, wheat, barley, oats, and grain sorghum, but higher than full costs for rice and peanuts. So in the corn example, farmers would lose money below full costs but not get any subsidy until the prices also fell below the Reference Price standard. Then they would get a subsidy for only a portion of the additional reduction, (for just 58% of the additional reduction in the example above).

A Potential Political Crisis for Farm State Republicans

Farm state Republicans in Congress, such as those on the Agriculture Committees, seem to believe that we’re heading for another farm crisis. We had much higher farm prices under Biden, but inflation from the pandemic plus the war in Ukraine caused farm input costs to rise a lot. This is seen in higher farm cost of production estimates from USDA’s Economic Research Service. Now many expect farm prices to fall. We see that in USDA and CBO projections, for example. That is what typically happens following unusual farm price spikes.

This translates into a potential political crisis for farm state Republicans. This potential is compounded by the fact that the Republican Project 2025 calls for ending the major farm subsidy programs, (Price Loss Coverage and Agriculture Risk Coverage,) and calls for reducing Crop Revenue Insurance subsidies, the sugar market management program, and the market agreement programs for fruits and vegetables, which have a supply management aspect to them. Project 2025 also calls for the elimination of various USDA programs. Meanwhile, President Trump has been implementing a number of Project 2025 provisions, and making cuts of various kinds to USDA.

Proposed Republican Reductions for the Price Loss Coverage Program

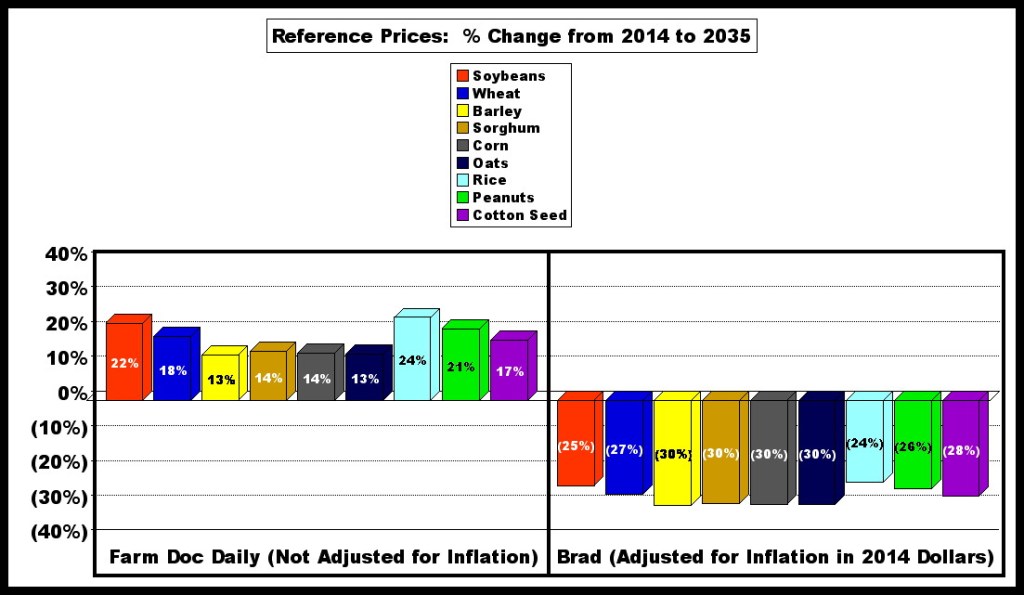

In response to the current concerns in farm country, House Republicans have proposed to “raise” Price Loss Coverage subsidy triggers, (Reference Price levels). For corn, for example, they propose a raise from $3.70 to $4.10. That’s a raise in nominal terms, (i.e. not adjusted for inflation). If adjusted for inflation, however, it’s a significant decline from the original standard of $3.70 in 2014.

The factor of adjusting for inflation or not has confused this matter. For example, the agricultural economists at FarmDoc Daily have claimed that the new Republican proposal raises Reference Prices significantly. Others have jumped on this bandwagon, citing FarmDoc Daily, and expressing outrage at the increased subsidies for crops like corn and soybeans, for example United We Eat, and the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Movement. I have challenged these claims, showing how, by adjusting for inflation, the PLC program standards have been significantly reduced.

Here’s what I find. As in the chart below, for the various crops, FarmDoc Daily contrasts the “Existing Statutory Reference Price” with the “Increase Proposed,” for example, the original $3.70 for corn versus the new 2025 standard of $4.10. The “existing” $3.70 could refer to the standard for 2024, or to the standard for 2014, or for any year in between. Because of inflation, however, the value of $3.70 in 2014 is significantly different from $3.70 in 2024. The same applies to the new standards. $4.10 in 2025 does not have the same value as $4.10 in 2030, according to CBO projections of the rate of inflation. Then, for 2031 to 2035, the House proposal raises the standard by ½ of 1% per year, to $4.20 for corn in 2035, for example. FarmDoc Daily ag economists identifies this “Increase Proposed” ($3.70 to $4.20,) as 13.61% for corn. Meanwhile, for 2031-2035, CBO projects an inflation rate of 2% per year, four times as much as the nominal Republican Reference Price increases for those years. So PLC Reference Price standards are also reduced during those years, if adjusted for inflation.

I’ve created two slide shows to tell this story and with multiple data charts for all of the crops covered in the PLC program. (See links in the References section, below.)

Farm Bill Issues Involve Significant Opportunities and Huge Challenges for Democrats

The PLC issue, in it’s larger farm policy and political context, as laid out here, offers significant opportunities for Democrats. Due to a major lack of knowledge of farm policy history and the history of related political activism, however, Democrats have a steep uphill battle to take advantage of these opportunities. This is not just a problem of what Democratic Party activists don’t know. The bigger problem is that Democrats “know so much that just ain’t so.” So there must be tremendous unlearning before a significant factual approach can be formulated.

At root, in multiple ways, Democrats and progressive activists generally have unknowingly been taken in by a conservative, Republican narrative about farm policy and politics. In the Republican narrative, the issues are all about farm subsidies and government spending. To “follow the money” you look at farm bill spending. That spending goes almost entirely to farmers, not to agribusiness, so the crux of the issue lies in what are believed to be large benefits to farmers, (farmer victims). Benefits to agribusiness exploiters tend not to be seen, or rather, they’re thought to come from farm subsidies. This is all essentially false, as can easily be proven. The biggest flaw is that the farm bill’s market management impacts, from severe reductions over decades, and which are much larger than spending and subsidies, are not found in government spending at all. In effect, they remain invisible to those immersed in this covertly, (unknowingly,) conservative narrative. And yet this much larger unknown part is directly where highly profitable agribusiness exploiters are massively subsidized. And so they are subsidized by these farmer victims, not by taxpayers, and throiugh them, consumers are also massively subsidized by farmers, especially by the subsidized farmers, and especially by farmers raising corn, and operating in corn belt states like Iowa. And the de facto subsidies that farmers pay to agribusiness/consumers are much larger than the government subsidies that taxpayers pay back to farmers as compensations. And meanwhile, as the U.S. so often loses billions of dollars on farm exports, there is very little awareness that it is occurring, let alone what caused it and what can be done to fix it. And the same applies to the massive subsidization of huge CAFO corporations, the resulting massive loss of farms with livestock and poultry, and the subsequent massive loss of farms and acreages of the greatly needed sustainable livestock crops, grass pastures, alfalfa and clover hay fields, and soil protective nurse crops like oats and barley.

We see then that there are numerous important corollaries that have arisen from this core, unknowingly conservative, narrative (which is rooted in dozens of farm subsidy myths, and see the reference for that topic below, as it explores various corollaries). For one thing, Republicans, and farm bills, (and especially Commodity Title programs, and especially farm subsidies,) are thought to be very pro-farmer. Both conservatives and progressives have believed this, in spite of the fact that it’s very false.

At the same time, of course, there are huge and increasing problems in agriculture, especially environmental problems related to pollution and climate, and health problems, but also the decline of rural communities. This part of the narrative is very true.

The narrative then puts these things together with a conclusion that the problems are caused by the farm bill providing huge incentives to farmers growing the main subsidized field crops, such as corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton and rice. The solution is then supposed to be found in “subsidy reforms” which cut subsidies to the vast majority of these farmers, and increase subsidies for conservation and sustainable farming practices. So the vast majority of farmer victims are seen as opponents who are supported by Republicans, and not as allies. Meanwhile, subsidy reform proposals maintain the disastrous Republican free market farm policies, (i.e. no New Deal style market management,) thus continuing to foster chronic market failure, providing the cheapest of cheap farm prices to subsidize CAFOs and agribusiness at the maximum possible level. So this imagined solution is hardly any solution at all.

One of the biggest falsehoods generating political failure on these issues is the lumping together of farmer victims with agribusiness exploiters, as if they’re on the same side, rather than on opposite sides. This is expressed by various ways by conservatives, such as by referring to the agricultural industry, or corn industry or hog industry. We also have conservative groups advocating on the issues in these ways, such as Farm Bureau, the National Corn Growers Association, the American Soybean Association, and the National Pork Producers Council. So these groups present themselves as farmer led groups, even though their approaches are pro-agribusiness and anti-farmer. On the progressive side, the same conservative narrative is widely expressed, such as with the terms “Big Ag” and “Industrial Agriculture.” In this way, by unknowingly utilizing a conservative, Republican narrative, progressives and Democrats are further divided and conquered. This is further reinforced by groups advocating for sustainable, organic and local farming and against “industrial” “commodity” “Big Ag” farming. In this narrative a nonorganic farm using tractors and combines is “industrial,” while an organic farm using tractors and combines is not. Additionally, in recent years much or most of the advocacy for black and other minority farmers has moved in this false direction and away from the previous unity of the Family Farm (Farm Justice) Movement. Livestock and dairy advocacy has also become siloed. The same is true for the anti-CAFO movement. Urban “Food” and “Environmental” influences have also been important to these intellectual and political failures. These leaders generally have lacked knowledge of the history of the farm bill and farm politics, or rather invented and spread a massive false history of it. (I base these generalizations on my having written more than 200 detailed reviews and review letters of the work of these various categories of activists, and on my many thousands of online interactions and tweets with representatives of these groups.)

Advocating FOR a Farm Crisis is a Very Bad Political Idea

Groups like United We Eat, which mistakenly believe that corn, soybean, and other subsidized farmers have been rewarded by historical farm bills, rather than penalized in total, in relation to other crops and enterprises, and which may also believe that subsidies cause cheap market prices, (they don’t,) have called for further reducing farm program benefits to these huge crops affecting hundreds of thousands of farmers across many states. What they call for, if enacted, could cause a major snowballing of the chronic farm crisis, especially in light of the fact that farm debt has risen to record high levels. This would be a disaster for agriculture, in many major ways, including with regard to the environmental problems. So this is a very serious misunderstanding, with major consequences, including political ones.

It would run many farmers out of business, leading to larger and fewer farms, which would further encourage the use of labor saving pesticides and fertilizers. It would do nothing to decrease the subsidization of CAFOs, and so would continue the increasing loss of the diversity livestock and the sustainable livestock crops mentioned above. As I’ve said, that then leads to more off farm work in order to survive, which again means less labor for diversity, and more off-farm capital for intensive input farming. This would all add to the loss of the infrastructure and info-structure for diversity, on farms, in rural communities, and across rural regions. That in turn hurts organic and local farmers. Beginning and minority farmers would be especially hurt. Both have been devastated by the farm program reductions of the past seven decades. There would be further losses of rural population and rural communities would see further decline, in multiple ways, as numerous studies have indicated.

Fortunately, there are great and unifying alternatives to be found in the model of the New Deal Farm Programs, as seen in the proposals being offered in recent years to update them. (One of the updates for which I’ve been advocating is to include incentives in supply management programs for helping to bring livestock out of CAFOs and back onto most farms.) Democrats have an awesome legacy to draw upon for this kind of an agronomic, environmental, social and political strategy. The key is for Democrats to learn about their own history of advocacy for just farm policies. As I’ve been arguing with regard to today’s social movement climate and narratives, in the big picture, there’s no significant farm sustainability without farm justice. And that’s what we find in the legacy of the Democratic Party: distributive economic farm justice.

References for This Price Loss Coverage Project

One value of this paper is that it provides further accessibility to the major reference sources that I’m relying upon in this PLC farm subsidy project. I’ve produced two major slide shows and two videos, and references are more accessible in this form than in those forms. Of special concern to me is the availability of this material to the Democratic Party, its leaders and candidates. The PLC issue being raised now by Republicans is a key indicator of the larger paradigm and narrative that can help Democrats to win back the rural vote. This in turn could make it much more possible for Democrats to win on a wide range of important issues unrelated to agriculture, including the protection of our Democracy from corrupt authoritarian and fascist influences. I’ve engaged in many debates with conservatives over these political issues over the past 40 years, and they really have no (Republican) answers to these challenges, where they are the big spenders who have long had us losing money on farm exports.

It’s not just that a renewed New Deal farm justice paradigm

My new work on Republican Reductions to Farm Program Benefits in the Reconciliation Bill

My Google Drive Folder with many materials: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1_AYKC9ICqz7vb5jfAQNmVjCQ3jVZbinN?usp=share_link

Slide Show: Brad Wilson, “Republicans Propose to Reduce Farm Subsidies,” Slide Share: Brad Wilson, 6/27/25,https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/republicans-propose-to-reduce-farm-subsidies-pdf/281074684.

Slide Show: Brad Wilson, “Extra: Republicans Reduce Farm Subsidies,” Slide Share: Brad Wilson, 6/27/25, https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/extra-republicans-reduce-farm-subsidies-pdf-ca8f/281556888.

Video: Brad Wilson, “Republicans Reduce Farm Program Benefits 1,” (“PLC Subsidy Triggers in the House Proposal,) YouTube: Fireweed Farm, 6/26/25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIiW3dgJmOg&list=PL6A69251AD0413A0D&index=1.

Video: Brad Wilson, “Republicans Reduce Farm Program Benefits 2,” (“More PLC Subsidy Triggers in the House Proposal,) YouTube: Fireweed Farm, 6/26/25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mg5QFCtf51E&list=PL6A69251AD0413A0D&index=2 .

Sources Claiming that Republicans Increased PLC Benefits in the House Reconciliation Bill

A number of Republicans in the House of Representatives have made this claim, including Iowa’s Zach Nunn and Randy Feenstra, and also Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins.

Schnitkey, G., N. Paulson, C. Zulauf and J. Coppess. “Spending Impacts of PLC and ARC-CO in House Agriculture Reconciliation Bill.” farmdoc daily (15):93, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 20, 2025, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2025/05/spending-impacts-of-plc-and-arc-co-in-house-agriculture-reconciliation-bill.html.

United We Eat, “MAHA Leaders Urge Rejection of Massive Subsidies to Big Ag in Reconciliation Bill,” United We Eat: 6/12/25, https://unitedweeat.substack.com/p/maha-leaders-urge-rejection-of-massive

MAHA, “To Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Stop Congress’s New “Big Beautiful Poison Bill” that Harm’s American’s Health,” United We Eat, June 6, 2025, https://unitedweeat.substack.com/p/to-make-america-healthy-again-maha.

More Information about the PLC, ARC, and Revenue Insurance Programs

Brad Wilson, “Dear Ag Sec. Perdue, Why are Peanuts Favored over Corn, Wheat, Soybeans, and

Oats?” Family Farm Justice, 7/14/17, https://familyfarmjustice.me/2017/07/14/dear-ag-sec-perdue-why-are-peanuts-favored-over-corn-wheat-soybeans-and-oats/.

Video: Brad Wilson, “Wilson V. Grassley 2: Farm Subsidies,” YouTube: Fireweed Farm, 9/11/21, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VAJyKU_d7sA&list=PLA1E706EFA90D1767&index=7

Slides: Brad Wilson, “The Case Against Bipartisan Farm Bills,” SlideShare: Brad Wilson, 11/16/22,

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/the-case-against-bipartisan-farm-bills/254542497.

Slides: Brad Wilson, “Democratic Party Farm Programs,” SlideShare: Brad Wilson, 4/23/22,https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/democratic-party-farm-programspdf/256537282.

Brad Wilson, “Primer: Revenue Insurance in the 2012 Farm Bill,” ZSpace: Brad Wilson, May 11,

2012, http://znetwork.org/zblogs/primer-revenue-insurance-in-the-2012-farm-bill-by-brad-wilson.

Brad Wilson, “Subsidies vs Price Floors in Farm Bill History, Revised,” Family FarmJustice, 5/25/16,

https://familyfarmjustice.me/2016/05/25/subsidies-vs-price-floors-in-farm-bill-history-revised/.

Learn About Reform Proposals

“The Farm Policy Reform Act of 1985,” 1985, https://familyfarmjustice.me/2016/12/10/the-farm-policy-reform-act-of-1985/.

National Save the Family Farm Coalition, “Family Farm Act of 1987,” https://familyfarmjustice.me/2016/12/09/family-farm-act-of-1987/ .

Video: National Family Farm Coalition, “From the Grassroots Up, Not from the Money Down,” YouTube: Brad Wilson: 4/13/21, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ywo1PX9VYI&list=PL7K_XwGI3jVS4AMDeEdFfHALIOYnoWg53&index=4.

National Family Farm Coalition, “Food from Family Farms Act,” IATP: Aug 28, 2006,https://www.iatp.org/documents/food-from-family-farms-act.

Dr. Daryll E. Ray, et al,

Rethinking U.S. Agricultural Policy, APAC: 2003, https://

www.agpolicy.org/blueprint/APACReport8-20-03WITHCOVER.pdf

Video: Brad Wilson, “How to End CAFO Subsidies,” YouTube: Fireweed Farm, 4/30/25,

Brad Wilson, “Primer: Farm Justice Proposals for the 2018 Farm Bill,” ZSpace: Brad Wilson,

May 11, 2012, http://znetwork.org/zblogs/primer-farm-justice-proposals-for-the-2012-farm-bill-by-brad-wilson.

Video Playlist: Brad Wilson, “Farm Bill History,” YouTube: Fireweed Farm, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7K_XwGI3jVS4AMDeEdFfHALIOYnoWg53.